Identifying and testing assumptions

When we think about innovation we quite quickly think about ideas.

We’ve all had brilliant ideas in our career. Ideas that we once thought were the best thing since sliced bread, that ultimately didn’t work out as we thought.

Any idea or hunch we have is informed by our own experiences and our own biases. And when it comes to working in complex local contexts it’s safer to assume that our assumptions are more likely to be wrong than right. Or at least a wrong enough to stop things working out as we would like.

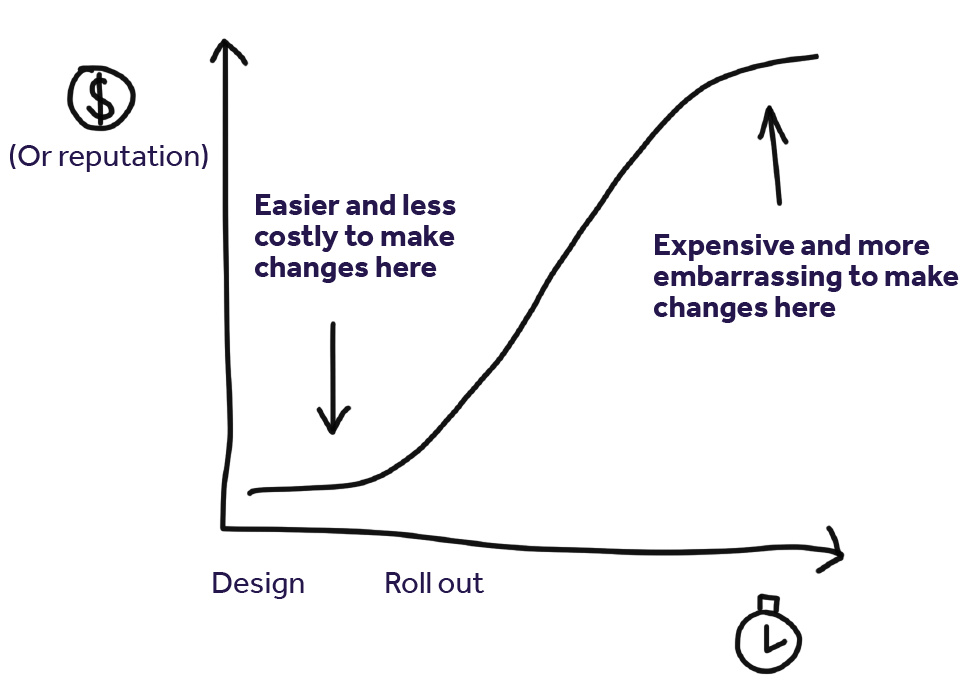

A good innovation process will help you rapidly test your assumptions in a cost effective way. People think of innovation as wild and crazy, but a good innovation process is actually a good risk mitigation process. A process that spots mistakes early, before time and money is invested in implementing things that were never going to work.

In the office / out of the office

Practically, testing assumptions means looping between ‘in the office’ and ‘out of the office’ work. ‘In the office’ we name and frame assumptions. Then we go ‘out of the office’ to test them in the real world with real community members. Design research methods and prototyping are two frequently used approaches to testing assumptions.

The more times we test and reframe our assumptions through real-world input the more likely it will be that our assumptions fit reality. The more likely it will be that we have an accurate understanding of community life and what will enable change in the community.

9 important assumptions for place-based social innovation

When you are seeking to create change through place-based initiatives there are three sets of important assumptions.

- Assumptions about people, their lives now and what people want for their lives in the future.

- Assumptions about the supports and services that will create change for people.

- Assumptions about the broader system and how place-based initiatives will shift that system to work more effectively.

When we say that ‘young people want local jobs’ we’re making an assumptions at the people level.

When we say ‘early interventions services will support local families’ we’re making an assumption at the service and support level.

When we say that ‘collective impact is the best approach to create change in our community’ we’re making an assumption at the systems level.

Assumptions may be wrong or right, and more often than not they are a bit of both. Assumptions may be informed by evidence of different kinds (research evidence, data, practice wisdom, lived experience) or they may be intuitive. We have to make assumptions, there is not progress without them. A good innovation approach will help by quickly identifying what’s wrong or right about them, avoiding investment into assumptions that don’t match reality.

Table: The nine key assumptions for place based systems change.

| Assumptions about peoples’ lives | Assumptions about supports and services in the community. | Assumptions about systems | |

| Assumptions about the current situation. | What is people’s lived experience now? Especially people experiencing marginalisation. | How do current supports and services help and hinder local people to live the lives they want ? | What are the elements interconnections, dynamics and boundaries of the system we are working in? |

| Assumptions about the desired future state. | What do people want for their lives? | What should future experiences, services and supports look and feel like? | What should be the elements interconnections, dynamics and boundaries of the future system? |

| Assumptions about the actions that will shift the current situation to future state. | What experiences might prompt and support people to realise the changes they want in their lives? | What actions could shift current services and supports into the desired future state? | What kind of place-based initiative could shift the current system into the desired future state? |

Tools for testing assumptions

Handily, for each of the three sets of assumptions outlined above there is a corresponding set of tools to help you test them.

- Tools from design research are particularly effective to testing assumptions about people’s lives and how services and supports work for them.

- Methods from service design, including prototyping, can help with visioning and testing future service models.

- Systems thinking tools can help you model systems (current and future) and identify effective leverage points.

- Tools designed for start-ups can also help you test assumptions about what model of initiative will work for you.

Facilitating meaningful and productive conversations

We’ve all been in meetings or workshops where one or more of the following happens:

- People go off topic

- Interpersonal dynamics or politics overwhelm or distract the group

- People who have less power, or who are quiet, don’t get heard

- There’s a lot of talking without making decisions

- The meeting feels tedious or pointless

These are all situations where facilitation can help. It is not always easy or natural for a diverse group to come together to work on something. Facilitation is the act of supporting a group to engage in meaningful and productive conversations. Typically one (or two) ‘facilitators’ take on the role of guiding the discussion rather than participating directly in it. A facilitator can create the conditions for productive conversations by:

- Preparing people to participate

- Planning a session to get to the desired outcomes

- Clarifying points that people are saying.

- Surfacing the wisdom and insight already in the room

- Enabling what is being said to inform decisions

- Keeping the group focussed whist balancing the needs of the group at that point

- Managing any conflict if and as it arises.

Results, process and relationships

A facilitator needs to hold three factors in balance. Facilitation helps a group move toward desired results using an inclusive and appropriate process, while attending to relationships:

- Results– The facilitator supports the group to reach the goal they have in mind.

- Process– The facilitator introduces and enables a process to inform the structure and flow of conversation.

- Relationships– The facilitator supports the group to maintain healthy and functional relationships.

The role of the facilitator

Effective facilitation requires a facilitator to design the conversation, lead the conversation in the room, and support making sense of the conversation afterwards. You may be able to find someone locally who does this regularly, or you may want to build your skills to do it yourself.

Whenever possible, try not to facilitate solo. Having two complimentary facilitators can help you ensure that the many dimensions of what is happening can be attended to: process, content, participant experience, relationships, politics, catering, room temperature, photos, etc.

A key role of the facilitator is to create a safe space, to foster an environment where people can come together safely both psychologically and emotionally, and as a result can contribute honestly and openly.

Facilitators who stay calm and collected (but not overconfident or arrogant) can help keep a group on track. People in a group will, for the most part, mirror the energy and mindset of a facilitator. However, facilitators who present to a group with an unclear, anxious or flustered mind will impact the group dynamic as a whole and negatively impact the conversation.

Facilitation is a craft best learned through practice. You can build your facilitation capabilities by:

- Reading this page, giving it a go and reflecting on how you do

- Read the resources in the more section

- Seeking out facilitation training. People have also found training in public speaking (eg Toastmasters) and in acting or improv helpful in contributing to their facilitation practice. )

- Getting coaching from an experienced facilitator.

Planning a session

Before any session deliberate conversations between the facilitator and stakeholders are critical in setting expectations, preparing participants and developing relationships for success.

Here’s a checklist for planning a session:

- Results.Work out what the groups goals and objectives are in order to understand why the session is occurring, the desired outcome and if the expectations are realistic.

- Relationships.Get to know the attendees, their history and their relative power so you can anticipate group dynamics. Plan how to ‘democratise’ the room by balancing out power. If not considered, some people may feel uncomfortable, and only the powerful will get their perspectives heard. This is particularly important if you’re bringing community members together with professionals of any kind.

- Process.Develop a session plan in advance. Different types of conversations require different plans. A good plan will support people to come together with ease, know what to expect and to get on with the conversations that will lead to the desired outcomes. ‘Begin with the end in mind’.

- Participant preparation.Inform participants of the sessions goals and getting their feedback and input prior to a session so that people arrive ‘on the same page’. Attendees may also appreciate pre-reading so that they are prepared for the conversation.

- Logistics and hospitality.Physical space, light, food and refreshments can all help to support an effective workshop. Look for a space that’s big enough, with good acoustics and natural light. Ensure refreshments are available and people feel looked after. Take care of dietary requirements.

Planning to involve community members and people with lived experience

Sessions where people with lived experience are involved require extra attention. In advance of the session:

- Support community members to understand the need and value of their contribution, seek to understand their motivation for participation and anticipate any factors that may make them feel uncomfortable in the session eg the location, the presence of professionals, language that might be used in the sessions.

- Prepare professionals to make them aware of their own power and take measures to check that power at the door, e.g. ensuring that they do not dominate the conversation, dress in an overly formal way or use language or acronyms that stifle community members understanding and contribution.

During a session

With the planning done in advance, during a session a facilitator focuses on supporting participation, and re-planning the agenda if required.

Here’s a checklist for running a session:

- Provide a proper introduction.Help the group understand the objectives of the meeting, the ground rules, and how they can participate.

- Recap on previous progress.If the group has come together reorientate people to the goal and help dispel any misunderstanding. In your recap focus on challenges, opportunities and outcomes. Encouraging discussion in order to refine and define progress is never wasted.

- Spell out or visualise the journey.This can help support groups to build their own momentum and reduce reliance on the facilitator to drive conversation.

- Support participation.Facilitators are constantly managing group dynamics. Facilitators may need to encourage quiet people and people with expertise to contribute more whilst controlling people that dominate the conversation.

Monitoring energy levels. Introduce activities and icebreakers when energy stoops and revitalisation is needed. Consider if session plans needs to be abandoned for another more appropriate direction. Ask yourself ‘what is best for the group to move forward?’.

Listen and call out the obvious. Stay focused and listen with an ear to the ground, judging if conversations are gaining depth and relevance, or going off track. - Surface tensions.Tension in a group is likely, especially when people are trying to solve problems. This is something for a facilitator to prepare for and manage. Tension can be destructive or productive, depending on the source of the tension, how it is handled and how participants respond. Getting a group to surfacing tensions and working through them can be a source of transformation and strengthen relationships in a group. Avoid tensions can mean missing potential breakthroughs and stifling relationships. A good facilitator will expose the elephant in a room if they have not been able to draw it out of a group. This may be an uncomfortable moment for everyone but avoiding the elephant can impact trust and prevent progression.

- Be prepared.Have a number of activities that you are familiar with that can support a ‘Plan B’ if the session needs to deviate from what was planned in advance. Some we particularly like are listed below.

- Provide closure.Take the group through a closure process so that everyone is clear on what has been achieved and the next steps.

After the session

After as session it’s the facilitator’s role to keep the momentum going, a facilitator’s responsibilities extend beyond the end of the workshop or meeting.

Here’s a simple checklist:

- Develop and share documentation from the workshop

- Debrief and plan next steps with key stakeholders

- Follow up with communication and further conversation

- Continue engagement and relationships

More

These resources can help you deepen your understanding of facilitation.

Seeds for Change – Overview of facilitation

Age of Awareness – ‘The need for facilitation’

Methods Library – International Association of Facilitators

Group Dynamics – Donelson R. Forsyth – University of Richmond

Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision-Making, Sam Kramer, 2018

The ideas and stories captured here were shared by members of the Regional Innovator’s Network during a peer learning session on 4 September 2018.

Unpacking co-design

In Australia today ‘co-design’ has become almost interchangeable with ‘consultation’. However ,the concept of co-design and the range of design based traditions that sit under the co-design banner have something very important to bring to place-based social innovation. Unfortunately, very few people have got to experience the true benefit of design-based approaches because co-design is rarely practiced authentically.

Co-design / co+design

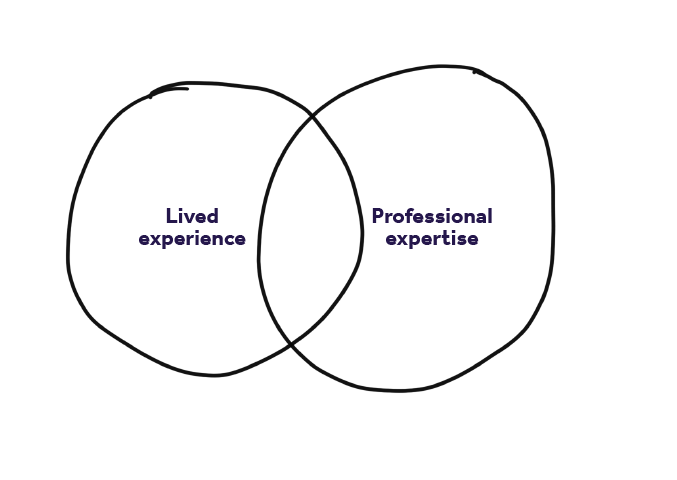

The ‘co’ in co design stands for community or conversation. It’s about bringing together people and professionals to jointly make decisions, informed by each others expertise. It’s not a community only activity or a professional only activity.

The ‘design’ in co-design is about making and testing, and this is the part of co-design that’s most often neglected. What most have happens is co (minus) design ie co-design. What we want to happen is co (plus) design ie co+design. Co-design without any making is just ‘co’. ‘Co’ can be useful, but it misses the rich learning and testing of assumptions that comes from making ideas (or representations of ideas) and testing them out in the real world, e.g. through prototyping.

Three traditions of design

There are lots of different ways to do ‘co-design’, although it’s often talked about as if co-design is a particular process. In fact there are at least three different design-based traditions that go under the banner of co-design, and unhelpfully they are often used interchangeably. Each tradition has its benefits and drawbacks.

Design thinking approaches are often workshop based. They tend to bring the community experience into the room for example through personas or user journeys. In design thinking approaches prototyping also tends to happen in the room and on paper. The brilliant thing about design thinking is that it fits easily with the ways organisations typically work. The drawback is that it can reinforce existing power structures and be less effective at challenging existing assumptions, meaning that it tends towards existing solutions. It’s a more incremental approach, and whilst the work is informed by lived experience decision making still rests with professionals.

In participatory design design approaches the design process is taken out of the room. A small group of community members and non-design professionals are trained to work together as a team to run a design process that may involve aspects of design research and prototyping. In participatory processes the design team (community and professionals) are given decision making power. Participatory approaches can lead to more breakthrough solutions, however they can require more time and specialist expertise to set up.

In human-centered (or user-centred) design approaches professional designers lead the process and make the decisions. Citizens and professionals are engaged throughout through design research and prototyping, but not necessarily the same team of citizens and professionals. The specialist capability required is greater than design thinking approaches and the processes can run faster that participatory approaches. However, special consideration will need to be given to taking communities along on the journey, as they are typically not the decision makers.

Whilst these are the traditions of design design-based methods can be easily adopted, adapted and combined. The best-fit design approach is the one that you can conduct with rigour within the time and money available. Participation done poorly can easily break trust with community rather than build it.

Learning about lives through design research

Design research is an approach and set of methods that are particularly well suited to understanding the reality of people’s lives, what they want for the future and how the current situations help and hinder them.

The limits of conventional consultation

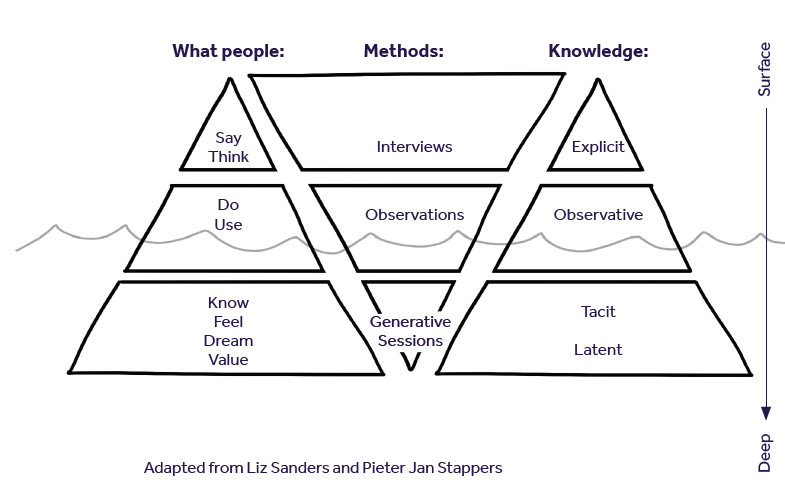

Common approaches for research and consultation include interviews, surveys and town hall meetings. Whilst these methods have their place they also have their limits when working on tough social challenges that require radical new solutions.

Large group ‘town hall’ type consultations can be effective when participants have the confidence to speak up, when problems are well defined and there are a finite set of solutions. However, place-based initiatives usually aims to meet the needs of people who may not have the confidence to speak up (because of a history of marginalisation) and problems and solutions are complex and hard to define. In these situations design research methods can offer a better way to understand people’s lives, needs and preferences.

To fuel innovation we need deeper alternative insight that can lead to breakthrough solutions. We need to learn new things to inform different things. However, conventional consultation often reveals surface level insight, what people thinkthey need. Henry Ford once said “if I had asked my customers what they would have wanted they would have said a faster horse.” Of course he didn’t go into horse breeding he developed the mass produced motor car. And he did that because he understood what people value – getting from A to B more quickly. It’s this type of breakthrough insight that design research strives to uncover.

Whilst a surveys might aim to validate 10 questions you already know to ask design research seeks to identify 100s of potential starting points for innovation.

How can design research help?

Design research typically happens in context (eg in people’s homes), uses small sample sizes eg 8-12 people, and engages 1:1 or in small groups. Sometimes design research involves spending hours or even days with an individual. Design research usually involves getting clear on the questions you need to answer, identifying who you need to speak to to answer those questions and then combining multiple methods to reveal the required data.

Observational methods like rapid-ethnography or user diaries can reveal what people actually do, rather than what they say they do. Generative methods in which people respond to stimulus, play games or design things can reveal what people feel, dream and value. And when you understand what people value, as Henry Ford did, you have great fuel for innovation.

Design research complements conventional consultation

Design research can be thought of as a complementary tool to large sample research and data sets, a set of methods that are particularly useful when engaging marginalised groups or looking to create non-standard solutions. Existing evidence, data and large-sample research (eg from surveys) can and (if it exists) should be used to inform design research. In turn, what’s developed by a small groups through design research activities can be be validated through a survey with a larger sample size.

More

You can deepen your understanding of design research through these resources:

- Slideshow and tools: An introduction to design research from TACSI – What is it, what does good look like and how to commission it.

- Tool: Buying and getting great design research.

- Slideshow and Tools: An introduction into personas, journey mapping and analysis methods

- Slideshow and Tools: A guide on good insights and how to develop them from design research and other sources.

- Book: Convivial Toolbox: Generative research for the front end of design, Liz Sanders, Pieter Jan Stappers, 2013

Identify ‘positive deviance’ to build on what’s already working

In nearly every community there are examples of situations that have worked surprisingly well.

For example:

- The teacher who out-performs their peers in an underperforming school

- The young person that got and is holding down a job despite the odds being stacked against them from birth

- The family that overcame addiction to become a vital member of the community

Identifying and understanding this ‘positive deviance’ will help you understand the kind of solutions that can work in your community – with the resources that are already in place.

Once you understand positive deviance you can start to think about how to put those conditions in place for the community members that don’t have them, for example through new kinds of supports or by spreading effective behaviours.

More

You can read more about positive deviance at

Reducing risk through prototyping

Making evidence informed decisions is critical to effective innovation and place based change. However, there is never evidence about what will work in your context tomorrow, and that is exactly what you want to know. Evidence is always from the past, and almost certainly from a different context. What works in the UK or USA isn’t guaranteed to work in Australia, what works in Bendigo won’t necessarily work in Ballarat. What works for teenagers won’t necessarily work for adults. What worked yesterday won’t necessarily work tomorrow. But it might. You won’t know till you prototype.

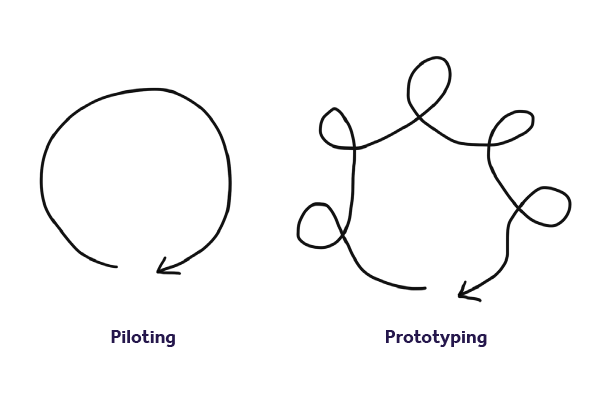

Prototyping can help you bridge the evidence gap by creating context specific evidence through experimentation. You can think of it as ‘rigorous trial and error’. Prototyping is the ‘design’ part of co-design. It involves making a rough version of what you think will work, testing it out, learning from that and improving your version over time.

Prototypes and pilots

When we pilot a new program we typically start with a model that has been designed, deliver that for 6-12 months and evaluate it at the end. In pilots there is typically one loop of learning. When we prototype something we undertake many loops of learning, and much more quickly. In prototypes things might change things on a monthly, weekly, daily or hourly basis. Prototypes help identify what works and what doesn’t quickly. Prototyping is all about efficient learning. Whilst the aim of pilots is to create outcomes, the aim of prototyping is to find what can create outcomes. Prototyping is often a pre-pilot activity.

The prototyping loop

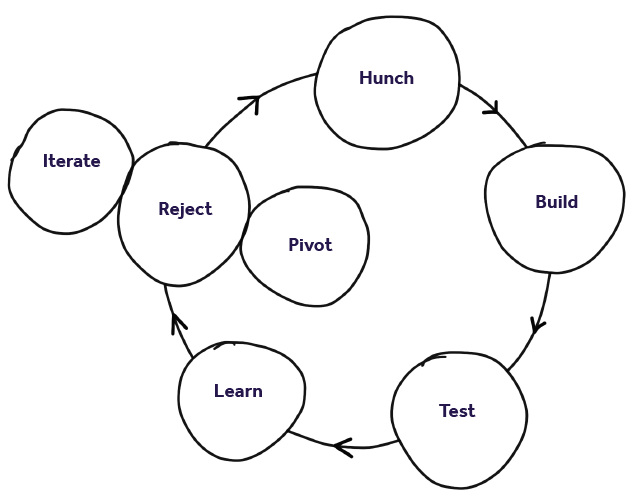

You can think of prototyping as a big loop of activity. You start with a hunch, or a hypothesis (if you want to sound fancy) or guess (if you’re honest). Then you build something, test it and learn from that test. If what you tested worked to some extent you might decide to iterateand do another loop of prototyping informed by what you learnt. If what you tested didn’t work you may decide to rejectthe idea and try something else. If it worked, but differently to how you expected you might decide to pivotand take things in a new direction.

Prototyping in practice

In the early stages of a design process prototyping can help you explore ideas. If you’ve identified ideas that are promising prototyping can help you refine them. When you really think you’ve got something that is nearly ready prototyping to validate that idea by running small scale experiments – a kind of mini pilot.

There are many different materials you can use for prototyping, each is suited to prototyping particular things. You can use paper, build things out on a tabletop, act them out, visualise scenarios or use frameworks for prototyping. You can explore more in the links below.

More

You can deepen your understanding of prototyping through these resources:

- Video: The making of Family by Family, TACSI, Australia

- Slideshow: An introduction to the principles and practices of prototyping

- Tool: A canvas for planning prototyping

- Article: Prototyping at McDonalds fastcompany.com, 2010. Service prototyping at McDonalds.

Adapting models from other contexts

Many of the social challenges faced in Australia are not unique.

Many of the challenges communities face — such as youth unemployment or increasing substance use — have, to some degree, been tackled in other contexts. Whilst solutions are unlikely to exist in a ‘ready to implement’ form, learning more about the thinking behind programs and initiatives with similar intent can have enormous value for our own problem solving. The adoption of effective non-local models into our contexts is an obvious way to maximise impact whilst saving time and money. However, it needs to be done with a degree of caution.

Whilst at the high level problems and situations are not unique, at the local level they are very unique. What has been designed for one context may not be readily applicable to another. It is also a possibility that something that ‘works’ in one context may be entirely unsuitable for another.

Services might not fit with local populations they aim to support. Something that is particularly relevant to in-community solutions where what makes programs and services ‘work’ can be very nuanced and intentionally designed for unique community needs. Seemingly minor factors such as branding, key messages, referral sources, or staff training time and techniques can be determining factors of success (or failure).

Services may not fit well into the local service system – with approaches to funding, performance management and local capability.

When program elements are not adapted but need to be, and other components are altered but shouldn’t be, the potential for success is undermined: University of South Australia found that when evidence-based interventions are implemented in other contexts, they often are “quickly adapted or changed, resulting in interventions potentially losing the key ingredients that were critical for effectiveness.” (Fiona Arney, Kerry Lewig, Robyn Mildon, Aron Shlonsky, Christine Gibson and Leah Bromfield, “Spreading and implementing promising approaches in child and family services” )

Research highlights that adaptation efforts struggle when “the links between service activities, their intended target group, the issue they are intended to address and their anticipated outcomes are not always clear.” Critical to a successful adoption is the integrity and soundness of a theory of change; research suggests that in a study of 52 child protection programs, successful programs demonstrated “integrity between target population, theory of change and program components.” (L Segal, K Dalziel & K Papandrea, Where to invest to reduce child maltreatment – a decision framework and evidence from the international literature, in Taking Responsibility: A Roadmap for Queensland Child Protection, 2013 (p 625))

Planning for adoption and adaption

The following questions are aimed to support initiatives to effectively adapt adopt and/or adapt programs, or elements of programs, into their own context. The questions aim to support teams to determine if adoption is a viable option and, if so, to identify what modifications are needed.

Nine questions to answer to support effective adoption and adaption.

- What is it that makes an intervention work in its original context?

- What is the core of the theory of change? What activities contribute to that theory of change and cannot be modified?

- What is the explicit objective of the program (e.g. what problem is it trying to solve)?

- Who is the intended target population and how is the new population similar or different that of the initial program?

- What are allowable modifications?

- What conditions need to be in place for an intervention to ‘work’?

- Are those conditions in place in the new context? How are conditions similar and different between the contexts?

- What allowable adaptions could be made to make the program fit in its new context?

- How can we minimise the risk, and maximise the learning associated with getting something working in a new context?

Practically this may play out over a number of stages:

- Understanding the intervention in the original context (including cultural considerations at each level of the implementation context from beneficiaries to staff and management)

- Understanding the new context and how it does and does not fit with the original context (i.e. characteristics, needs and preferences of target population)

- Deciding and designing adaptions for the new context (i.e. which also includes the implementing agency’s practitioners, organisation and wider service environment)

- Prototyping a modified intervention in the new context to contain risk, refine design, and surface further adaptation needs for optimal efficacy.

- Full implementation of adapted model in new context (i.e. including staff section, training, coaching and supervision, performance evaluation and assessment, data systems to support decision-making, and facilitating adaptive leadership)

- Oversee and monitor program drift and implementers’ responsive revisions

The process described above is clearly relevant for the adaption of models from overseas into Australia, but similar principles, at a smaller scale, can be applied to adaptions for different communities within Australia.

A TACSI example

TACSI’s own program Family by Family, underwent a series of intentional adapts to make it work in the North of Adelaide, after being initially developed in the South. Following research with communities in the Northern Suburbs we identified the need to change the language used in the recruitment of families and to change how the families came together as groups. The later because of a very different transport situation. Had the model been delivered identically in the North as it was in the south we are confident it would have failed. Even thought the two communities are only 45 minutes apart. Now the program in the North regularly out-performs the program in the South.

Fundamentally, solutions need to work within the context for which they are delivered, which requires a careful acknowledgement of cultural and behavioural nuances. Any attempt to move to another context should follow a rigorous process of adaption which both respects the core of what makes the service ‘work,’ and utilises ‘allowable adaptions’ to ensure that it is effective and maintains fidelity in its new context.

Design new services models for impact and sustainability

When it comes to designing services and experiences tools from service design, evaluation and start-up thinking can be used in combination to ensure that we’re developing something that works, something that people want and something that will be sustainable in the long term.

The tradeoffs

Being a customer is a very familiar experience for all of us — holding a customer experience perspective can help us understand what makes a service that people want to use and keep coming back to.

Let’s take buying a coffee as an example.

For a coffee shop to succeed, it has to have a product (coffee) that people want. It must also be a great experience that people want to return to. And, it’s got to be profitable enough to stay open. The balance of these three elements make a successful service and a successful business.

If you were running a coffee shop you could try to improve your product by buying better beans and hiring a more experienced barista. However, if the price of coffee stays the same, the quality of service may go down because you’ve got less money to invest in the upkeep of the premises or in serving staff. Increase the price of the coffee, and you’ve got a stronger financial model on paper, but you may start losing customers to your more affordably-priced competitors.

With any of these situations, the risk is that your customers aren’t happy. They’re not getting what they want, and neither are you. As a result, your business struggles. Without a sustainable business, you can’t grow; you can’t create the impact you want for your customers.

It’s notoriously hard to run a successful cafe. Designing a successful community-led initiative or social service is even more difficult.

In a coffee shop, you primarily have one customer: your coffee drinkers who decide where to buy and what they’re willing to pay. Social services typically have 4 or 5 different customers, each with a different kind of influence on decision making. This may include the beneficiaries of the service, their families or carers and paying customers – the funders.

Three innovation views and tools

Teams designing in the complex place-based settings can keep in mind three views to steady their course.

- Impact View:Taking this perspective will help you focus on developing services that create transformational change and value for people.

- Sustainability View:Taking this perspective will help you develop services that are desirable, feasible and viable now and into the future.

- Experience View: Taking this perspective can help you develop services that people want and delight people.

For a successful service and business all three aspects need to be in balance. Each of these views has a handy tool to help you apply it to your context and organisation

Impact — Theory of change

‘Theory of change’ frames the impact perspective. It answers the questions: how does what you do lead to positive impact for people? Theory of change helps you and your organisation create a clear story about impact.

A tool drawn from evaluation and social science, theory of change usually involves developing a diagram that steps out how certain activities lead to intended or unintended outcomes. Once drawn, it helps you test the logic of your model.

Our monitoring and evaluation friends at Clear Horizon emphasise that “The key is to try to think in terms of ‘outcomes.’ – how will your activities in turn lead to small changes that in turn lead to changes in health or wellbeing for people.” This kind intentionality helps you check if your interactions create ongoing value for people — and which activities might not be leading to something very useful at all. The theory of change holds you to account for meaning what you say and saying what you mean. The theory of change also helps you be explicit about the difference between the actual impact of your service and a larger vision you hope to contribute to.

Here is a theory of change template; it can be used for current services or to visualise a future, better service you’re developing.

Sustainability — The Business Model Canvas

The business model canvas and back of envelope calculations frame up the assumptions about the sustainability of your service or enterprise – is it desirable and feasible and viable. Do your customers want it (desirability), can you deliver it (feasibility), do the numbers stack up? It’s a canvas developed by consolidating many frames into one handy tool.

The business model canvas is often complemented by a back of the envelope costing. The back of the envelope zooms in to the bottom boxes of that business model canvas by listing costs and revenue of your business’ core functions. This kind of simple math is how Elon Musk (CEO of Tesla and SpaceX) pitches solutions that seem conceptually impossible. He’ll run back of the envelope calculations for cynics to prove you actually can transport people underground at 200km / hr — and you can do it for less money than what it would cost to renovate the subway system. Whether you’re transporting people in innovative underground tunnels or to a doctor appointment, knowing cost and revenue gives you leverage to make decisions about financial risk and safety.

The business model canvas developed by Strategyzer and used by businesses around the world.

This is the ‘back of the envelope’ template to help you lay out costs and revenue and make rough estimates about the financial viability of particular service.

Experience — Service Blueprint

The service blueprint visualises the components of service or business. It details what people will think, feel, say and do before, during, and after a service experience. (Remember that great, well-priced coffee with rude staff and insufferable queues is not a business.) The service blueprint looks at the service experience from a user’s perspective and documents what needs to happen. It’s also a framework to help other locations replicate quality and practices from one site to many.

To create significant change you’ll need more than a good service, you’ll need a great one. We’ve learned how people using services trust word-of-mouth recommendations from friends and trusted others most. As a service provider, you’ll want to make sure people have good things to say about your service experience. Sometimes it’s small things like biscuits or a warm welcome at the door that make the difference.

Here’s a basic template that you could write in, digital versions are also available.

These three views are intimately intertwined. Each activity in Theory of Change should have a considered experiential design within the Service Blueprint. And each activity within your Service Blueprint relates to some sort of cost, revenue, channel or partnership within the Business Model Canvas. Any change in one of the three views will affect the other two. In our experience developing services across sectors (disability, child protection, home and housing) balancing experience, impact, and sustainability is what sets great services apart from mediocre, short-lived ones.

There’s lots to think about when you’re developing a new service. If you’re going to do just three things, keep the balance between impact, sustainability, and experience in mind.